|

|

|

|

Interview with Vladimir Vasilyevich Titovich by Oleg Korytov and Konstantin

Chirkin.

Redactor: Igor Zhidov.

Special thanks to Svetlana Spiridonova, Ilya Grinberg, James Gebhardt,

Ilya Prokofyev and Oleg Rastrenin.

|

Seniour Lieutenand Titovich, 1944 |

I was born on March

5th, 1921. I am a Ukrainian, and I was born in Ukraine, in the village

Avdotino, a suburb of Donetsk. Donetsk used

to be called Yusovka, then Stalino, and now it’s Donetsk.

My family consisted of me, my brother, my

sister, and my parents. My mom was a housewife. My father worked at Kramatorskiy

plant from

the age of 13. I asked him: — How

could you work at such a young age?

He replied:

— When you want to eat, you will start working. My friend and I had

to carry metal leftovers from the plant.

When I was young, my health was rather poor.

I was frequently sick, and because of this I had to go to school quite

late. When it happened

we were already living in Kramatorsk. I studied through the eighth

grade, and after I celebrated my 16th birthday my dad convinced me to start

working. For four months I studied at FZU[1], and then started working.

I must have been a good worker, because many years later I was awarded

by a memento gift and a medal «50 years to Novokramatorskiy mashinostroitelnyy

Zavod»[2].

I worked until 1940, at which time I enlisted

in the Army.

—You were called to arms?

No, I voluntarily enlisted for the Voroshilovgrad military pilot school.

When I was working at the plant, I joined the aero club. It was 1938 or

1939. A lot of my friends also signed up.

I worked and studied at the aero club at the same time. It was not

so far from our plant. When we began flying, the aero club started sending

a bus after us. It was good if we worked through the first shift; second

shift was a bit worse; and the third – when you had to work through the

night, was the worst. I had to go to the aero club straight from my working

space, half asleep.

I studied in the aero club for two years and finished it with excellent

marks. In 1940 I applied for Voroshilovgrad flight school.

—Which planes did you fly in the aero club?

U-2. The famous kukuruznik [cornfield hopper]. You could land

it on any road, any spot in the forest, even in the garden.

—Were you issued a uniform in the aero club?

We had no uniforms. Everyone wore what they had.

— Voroshilovgrad school trained pilots for which duty: fighter pilots

or shturmovik [ground attack] pilots?

It’s hard to say. We were trained for three types of aircraft. But

we started from the “young soldier’s course.” For us it turned out to be

a construction project. We built a large shooting range to check gun convergence

on the planes. We worked an entire day for several weeks.

Then, since we were already trained to fly the U-2, we were sent

to train on the R-5. Then: “No, this is an obsolete plane.” We started

to train on the SB bomber. When the war began, we were transferred to Uralsk.

There I finished training on the SB. We could be sent to the front, but

by this time the “Hunchbacks” appeared, and a need arose for shturmovik

pilots[3].

— When was your school moved to Uralsk?

I don’t remember exactly; in 1942, perhaps, when the Germans

were getting close to Voroshilovgrad. I remember that because of this evacuation,

I was not allowed to attend my father’s funeral.

Instructors flew airplanes, while students had to march to Saratov

by foot fully loaded: greatcoat, rifle, gas mask, and so on. During first

day we marched 42 kilometers and reached the KalachRiver. Most of us immediatelly

threw our gas masks in to the river – they were way too heavy.

Then we were loaded on the train and sent to Uralsk.

|

Voroshilovgrad aviation school, 1943

-, Darnitskii, Nikolay Shukin, -, -, Titovich |

—You flew on the R-5, SB, and later on Il-2. Which of these planes

was more comfortable, easier to fly for the pilot? In terms of piloting

qualities, not combat, I mean.

The SB was a very good plane. It was called “twin-engined pike”. When

it flew, its engines made a “sh-sh-sh” sound. Excellent airplane, very

comfortable and beautiful. Silver colored... They had previously fought

in Spain, but for some reason they were too vulnerable to enemy fire. If

it was struck by bullets or shells, it would catch fire way too often.

It suffered big losses[4].

— When were you directed to train on the Il-2?

At the end of 1942, I think. I left the school in 1943.

— You were trained on a dual-control UIl-2?

Yes. The instructor sat behind me, in the second cabin, while I had

to familiarize with the plane from the front cabin. The instructor had

only a stick and minimal instruments, while I had a full instrument panel,

throttle control, and plane control stick.

— What was your first impression of the Il?

It was a pity that we had to leave the SB behind, and we felt

that the Il was too heavy. We didn’t trust it. We had no idea what this

plane was capable of, how it would show itself in combat. We had to learn

to land it: other planes would simply glide to the runway after you closed

the throttle, but this one required some throttle to be applied. The Il

was a bit more difficult to fly. But after we flew it for some time, we

felt more or less comfortable with it.

—What was included in the training program: Flying, combat maneuvering,

group flying?

At first we were taught to fly: take off, landing, “box,” “zone.” Then,

when we began to feel the plane, we started to perform aerobatics elements.

But the Il couldn’t make a Nesterov loop. Well, we were taught to fly the

plane in all modes. Then we started to study its combat use.

We had a special field with a cross and a circle on it. We used to

bomb and shoot at it. The guns were zeroed at the shooting range that we

built previousely.

—Did you use live bombs for practice?

No, concrete bombs filled with water. When they hit the ground they

would break apart, and you could see the spot they hit.

—Did you aim while bombing, or did you drop bomb at the moment that

you felt right?

There were two stripes on the cabin, and you would drop your bombs

depending on which altitude you were at. It was a very primitive aiming

device, and to use it well you had to gain experience. But we trained with

the seellipses first[5].

After we learned, trained, and had war experience… I remember, there

was one incident near Parnu, Estnia. We flew the new Il-10 then. The commander

asked:

— Who can hit this hay pile? And we blew this pile to pieces

with small bombs. The owner of this hay came to us and made complaints

later.

— How many hours did you spend in the air and how many flights did

you make while training at the flight school?

I don’t remember how much I flew on the R-5 or SB, and I also don’t

remember when I flew on the Il-2 without an instructor.

But I remember well my first solo flight. At aero club I was allowed

to fly the U-2 solo after 41 flights. When I took off, I can’t even describe

what happened to my heart. I was a kid when I saw an airplane the first

time, and felt an urge to fly. And here I am – piloting an aircraft! And

I have to note that it was totally free for us! I flew, and I could see

all of Kramatorsk from above. I even could see the building where I worked!

“Oh, — I thought, — what a beauty!” . How

many hours I had flown before I got to the front, I don’t remember, and

there is no way to restore it. I used to have a pilot’s logbook, but after

the War’s end, in the 1950s, “rooms of combat glory” were organized in

the schools[6], and their representatives kept coming to me: “Do you have

photos? Give them to us! Control stick? Give it to us! Maps? Give them

too!” They took everything they could… I was in luck that they didn’t take

my pants from me. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union, they simply

threw everything away. Nowadays they are coming to me once again, but there

is nothing left to give them. And what if government changes its course

again? Will everything that I gave them be thrown out one more time?

— At what rank did you finish flight school at Uralsk?

After graduation I received the rank Junior Lieutenant.

— When did you receive Lieutenant?

It is noted in my military identification booklet. Recently I received

the rank of colonel; girls from the voenkomat called me:

— Come to the voenkomat, we will make a note in your military identification

booklet, that you are a colonel of aviation.

But what good will it do me if I have this note? Lately I sit at home all

the time and I haven’t flown for ages.

— When were you sent to the front?

It was in May 1943, if I’m not mistaken. Our group of 10 men was sent

to Kuybyshev, where Il-2s were made. There I received a plane. They all

were similar, new and shiny, with new paint.

I checked for the plane’s condition, signed the required papers, and test

flew the plane several times. There were some defects in the plane, but

after each flight the mechanics fixed them, and I flew it once again to

cross-check for previously undetected problems.

When all the new planes that we received had been tested and found

ready for action, a Pe-2 was given to us as a lead aircraft, and after

taking off we followed it from Zubchaninovka airfield.

— Did you receive a two-seat plane?

Yes. Our leader brought us to Khvoynoye near Moscow, where a ZAP [reserve

aviation regiment] used to be based. There, in 2nd Training Squadron, we

were taught to fly in formations, bomb targets, and shoot at them. After

a month of training, six men were sent to the Leningrad Front, to a place

called Budogosh. Once again a Pe-2 led us to the airfield Gremyachee.

I don’t know why, but we were there for a rather short period of time.

Then we flew to the VolkhovRiver, to the village Ezheva, which was located

approximately 40 kilometers from Volkhov. Our 872nd ShAP was stationed

there. Our pilots flew from there and suffered losses.

|

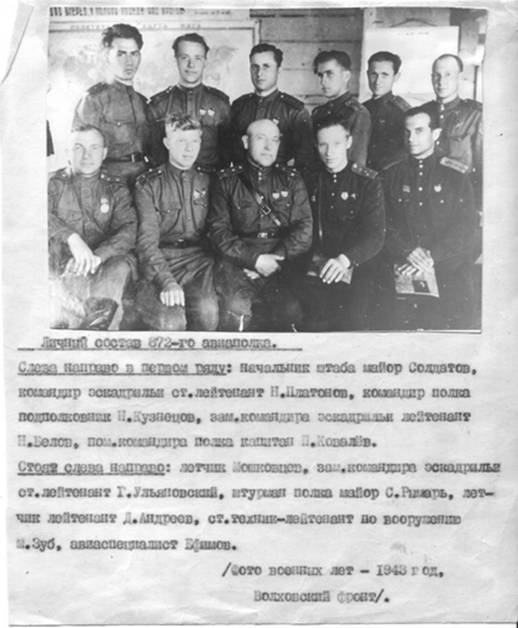

During combat activities at the Volkhov Front, Winter

1942-43

Third from the left – Belov, fourth from the right - Platonov |

— Do you remember when you arrived at the combat unit?

June of 1943. It was warm that day.

|

Chief of Staff Soldatov standing on the left

1st row: Khristolyubov, -, -, Titovich, -, -, -, -, 2nd row: -, -, navigator A.P. Rymar, -, -, Ognev, -, Platonov 3rd row: -, Tripolskiy, -, Andreyev (half-turned) |

— How you were greeted at the regiment?

You must have seen the movie “Only Old Men Go to Combat”? That’s how

we were met. This movie is the most correct, most honest one without any

“added heroism.” Everything is shown there correctly… We were the same

«grasshoppers»… We were completely alike. We were lined up

as in the movie, and the announcement was made: — You will join 1st

Squadron, commander – Senior Lieutenant Belov.

I remember my commander’s first words, and they once again resemble

the movie: — Wherever you are, alone or in a formation, your head must

be rotating 360 degrees. Otherwise you will miss the enemy fighters, and

you will end up being killed.

|

Navigator Rymar (in the blouse) provides briefing before combat sortie |

— Was there a rear view mirror in Il-2?

No. And there was no mirror in Il-10 either.

— Did head-protecting armor obscure your rear view?

No, I wouldn’t say so.

Here is Nikolay Belov on the photo — A good and very honest lad… I

won’t forget him.

For about a month we were studying the situation, and did nothing.

Meanwhile our regiment kept fighting and suffering losses. Both planes

and pilots were disappearing. At first we

studied the area around our airfield and battlefront. The situation was

shown to us on the map, and later we flew there: — Here is the battlefront,

here are the hills, that’s the VolkhovRiver... And so on and so forth.

When we flew “boxes,” our squadron and regiment leaders tested our flight

technique. Then we received planes.

— You ferried in two-seat Il-2s with gunners, or gunners were appointed

to you at the regiment?

Of course we flew alone. And later we had to ferry planes from Kuybyshev

several times. And each time there were no gunners. There was no sense

to take them on such trips. When we returned to the regiment, my gunner

would check his weapon, clean it, and then he would fly combat missions

with me.

When we arrived in the regiment, we knew nothing and we could do nothing.

Because of this, new planes were given to the more experienced pilots,

while we received old single-seat planes.

— How you were informed about your first combat mission?

It was July or August, near Mga, during an attempt to lift the blockade

from Leningrad. In February it was announced that the blockade had been

lifted, but it was more for raising spirits – only a 10-kilometer gap had

been breached in the enemy lines, and it was under constant barrage fire.

The Germans had a lot of fortifications near Mga, and several Shturmovik

regiments fought there. The fighting was fierce. We bombed Mga for several

days. We used to say that when we came to the Mga area, the compass arrow

started to show “other world,” because of the metal that had been thrown

to the ground. There used to be a railroad bed, and as long as our forces

were trying to cross it, we reduced it to ground level. There

were almost no German fighters there, but AAA fire was very strong. Heavy

AAA

guns were stationed at Sinyavino, and after we dropped our bomb load, they

would try to hit us on the pullout. They used to leave a trail of black

explosions after us.

Belov gathered all the young pilots and said:

— We won’t take you all to combat at the same time. We will introduce

you to battle one by one. Today we will be flying in a four-plane formation,

and Titovich will be flying fourth plane. Your main task for today — do

as I do. Listen to the radio. When I will say: “Fire!” — fire. When I say:

“Drop bombs!” — drop them. But keep in mind, that the main task for the

last in group is to stay on the leader’s tail.

The last in the formation usually gets it all. On my first combat day,

on the third sortie I got 5 holes. AAA hit me. Gemans had 37mm automatic

cannon, loaded by 5-round magazines. The German pressed his pedal, and

all these rounds hit my plane.

My airplane fell from 800 meters almost to the forest, and I only recovered

near the ground. My plane flew home “sideways.” I made it to the airfield,

and landed. Batya came to my plane and said:

— Congraulations! This was your baptism by fire. If you were shot up

on the first day, but you are still alive, it means that you will live

till the end of war.

We took a photograph, and then technicians told me:

— Move aside! And my plane was towed

to the bushes by tractor. I almost cried when I saw it!

So I kept fighting on the other planes, if other pilots for some reason

didn’t fly.

In time, when there were few planes left in the regiment, our commander

would arrange a group of 5–6 pilots, and we would fly to Kuybyshev. I flew

in such groups several times. There were three airfields packed with new

planes: Zubchaninovka, Smyshlayevka and Bezymyanka. We would pick up planes

there, test fly them, and then we would fly to the front.

|

3rd combat sortie. Il-2 was hit by 5 37mm rounds. Pitch controls are damaged, left longeron was broken, aerilon was torn to pieces, right cannon torn away, rear upper armor torn away, not to mention small holes in the fuselage and wings. |

— Was the quality of the new airplanes good enough, or did your technicians

rebuild them?

Mechanics at the regiment didn’t rebuild them. When I received a new

plane, I walked around it, opened all hatches, looked inside, checked the

controls, and test-ran the engine. If instruments showed that everything

was normal, I would make a test flight, and only then would I be able to

say if everything was fine. Every system had to be tested in the air. If

I found any deficiency in the plane, I would inform the technician about

it: — This has to be checked, that has to be tighter...

The mechanic would do all that I told him to do. Then I would make

another test flight, and tell him: — It’s fine now! Now we can go to

the war!

|

Il-2 engine is being repaired in 872nd ShAP. |

— Were there cases when you would test fly the plane, and feel

that it was not good for you?

No, never. I would trim the plane, and usually nothing else was needed.

— You ferried new planes several times. How much time did it take?

We would take off from Kuybyshev and make a stop at Vologda. There

we were refueled and had a night to rest.

— We heard that sometimes ferrying lasted a long time because of

lack of fuel on the intermediate stops. Is this true?

We never were late because of lack of fuel, but it did happen because

of the weather. We could spend several days in Vologda. There was a good

brewery there and a great beer. To fly or to stay was a decision of the

flight leader, usually a squadron commander. Next time we would land at

our airfield. We were always led by a Pe-2. He would fly at the front,

while we were trailing him.

— So, it took you two days to reach your home base?

Yes, we arrived on the second day. But it depended on the weather.

Once we had to stay for a week at the Vologda because of fog. We were not

able to fly on instruments; we were unable to fly “blindly.”

— Did weather alter your actions on the front?

Of course. The Il-2 instruments allowed us only visual flying. We didn’t

fly in bad weather. If you would open the small window, then you could

see to the left. But that was not enough [7].

—When did you become a true shturmovik pilot? When did you begin

to see the air and the ground? When did you begin to shoot not in the general

direction of the enemy, but at the targets?

You have to get used to it. This was exactly why we were placed to

the end of the formation. After you have flown several times, you begin

to see the situation. It usually took 8 to 10 flights. You also have to

get used to the AAA and fighter threats. And only then will you be able

to see where to shoot and where to drop your bombs[8].

— What kind of armament did your first plane have?

Two 23mm cannons and two 7,62mm ShKAS machine guns.

— Did you have a PBP 1B gun sight? Or was it just lines on the windshield?

There was a gun sight on the canopy, but which and when... I simply

don’t remember. It was over sixty years ago…

— What was your usual bomb load?

Our maximum load was 600 kilos. When we tried to breach the Mannerheim

line in Karelia, we carried two 250 kg bombs each. The fortifications there

were so strong, that even FAB-250 were considered as inadequate.

— What altitude was used for bombing?

We approached our targets at 600–800 meters; it was the standard altitude.

For bombing and strafing we would dive to 200–300 meters. But it could

be different. It depended on the target type, its cover, and so on. There

were a lot of “buts.”

— There are different opinions about RSs [rockets]. In your regiment

RSs were considered to be an effective weapon?

Why not? The RS-82 and RS-132 – flying “Katyusha”, was very good weapon.

Four on each wing.

— Some say that RSs were difficult to use and to aim. Is this true?

It depended on the rocket quality. If the RS was good, and its fins

were not bent, you could hit pretty close, 3–5 meters from the aiming point.

But if there was a defect, you could see how the rocket would change trajectory

to the almost opposite direction.

— Which weapon of the Il-2 did you personally consider to be the

most effective?

Well, it depended on the target type. If we hunted tanks, we would

carry small cumulative [shaped-charge warhead] bombs. We also used VAPs[9].

It’s granulated phosphorus with water. When we opened the VAP, it would

contact with air and ignite. It could set on fire anything it touched,

even tanks. We used these VAPs at the Volhov front. We received the mission

to burn German supply dumps near Pomeranye railway station. We approached

the target in a six-plane formation at an altitude of 50 meters. There

were no AAA guns there, so we divided into pairs and sprayed these warehouses

with phosphorus. They immediately caught fire; there were several heavy

explosions. It looked great. I think the Germans must have been impressed

as well.

— And how often did you use VAPs?

Only this one time. They produce a lot of drag, otherwise they’re a

very good thing.

— What do you think about 37mm cannons?

They shot well. Our planes had two 37mm cannons. I remember how they

fired when we strafed trains retreating from Novgorod to Pskov. I was sent

to the Dno-Porkhov area with three other pilots. We hit them good, and

saw smoke from the train. They used to have AAA on flatcars, and they shot

at us. They shot at me, and I shot at them. They missed us, but we hit

them.

— Some shturmovik pilots that we have talked to complained about

severe recoil that on some occasions caused the wings to be damaged.

You know, I never saw such cases. 37mm cannons were attached only to

all-metal airframes at the end of the war[10].

— Were you satisfied with 23mm cannons?

I used them for almost entire war. They satisfied me.

— But you liked 37mm more?

You see, the situation is a bit more difficult: there were only about

50 37mm rounds, while the 23mm cannon had at least twice as much ammo.

37mm was great on large, well-armored targets, such as trains, a little

bit worse on tanks due to large dispersion because of recoil. But if you

are strafing a road vehicle column, it is preferable to have cannon of

smaller caliber, but with higher rate of fire and more ammo. 23mm was a

more universal weapon.

— Did you make photographs to confirm strike results?

Of course. To control our strafing run results there was a gun camera

fitted near the landing gear nacelle. On a developed film one could even

see the tracers and where they hit the target. If I dropped bombs, then

another camera would start filming where they were falling.

— Were there cameras on each airplane, or was there a specific plane

in the group?

Good question. When we flew to strike an airfield in Finland, I was

the only one with the camera on board. It happened during

the Vyborg operation. Enemy air forces were handicapping both our air

and ground force operations. We started striking their airfields in six-ship

formations. One group hit the field, another one also unloaded. We covered

the airfield well; everything on the ground was burning, here and there

there were explosions. I came last and alone to the target. I had to fly

at the altitude of 800 meters “without movement” to make good photos.

My gunner, Volkov, says:

— I see two enemy fighters.

I replied:

— Shoot at them!

We keep flying steadily and filming the results.

I hear another report: — Two more Finnish

“FD.” There are four of them now… And here is the third pair coming…

At this moment, Volkov stopped shooting.

— Why you are not firing?

— My machine gun has jammed.

By this time we had finally finished filming,

so I dove to tree-top level. We flew right above the heads of German and

Finnish soldiers. If enemy fighters would try to shoot me down, they would

try to approach me from the rear and below, and I denied them this possibility.

They did not know that my gunner’s machine gun had jammed, so they were

not too eager to attack from above.

Volkov tried to help as he could:

— Look behind you — he told me, — now you’ll have to make a sharp

turn. He’s attacking!

I made a turn, and saw a tracer fly by on

the left. He also confirmed that a tracer missed us on the left side.

— I suppose you were not so calm at that time, as it appears from

your story now.

There was no sense in becoming over-excited either. If you panicked,

you would make a mistake, and then they would eat you alive, and they won’t

choke. I kept maneuvering this way to the Vyborg front line, and quickly

reached it. As I flew over the front line, some fascist hit me in the engine

– the bullet flew between the engine cover louvers. I had no idea if it

was the fighter or ground fire – it could be both. At this moment our AAA

opened fire at the enemy fighters.

So bullets hit my oil tanks. There used to

be two oil tanks on both sides of the engine compartment with 91 liter

of oil, if I’m not mistaken[11]. So I saw how oil was spreading on the

floor, on the canopy, the instrument panel. Oil was everywhere. I started

to gain altitude and noted that the oil pressure was falling and engine

temperature was rising. I thought: “Damn! Where we are going to fall?”

It is not the best idea to crash-land on the Karelian Isthmus. There are

a lot of boulders in the forests, and if you hit one with more or less

high speed, this will be the end. Thus I

kept climbing higher and higher. I couldn’t bail out – all the regiment’s

work was on the film, and if I lost my plane, the results would remain

unknown. So I flew toward home. We came to our airfield, altitude 350 meters,

and I started to reduce throttle. And I made it! The engine stalled when

I lowered landing gear and flaps, somewhere at about 20 meters above the

runway. So the plane landed, and started rolling out. I couldn’t see anything,

and couldn’t steer the plane. When we stopped, I looked out. We had rolled

straight to the command post. The canopy,

the entire airplane was black – it was covered with oil from nose to tail.

Oil begun dripping from the fuselage, and a strip of oil started to appear

under the plane. I crawled out, covered in oil like a goose in gravy.

People came running to my plane. A technician

came to me, and gave me a piece of broken mirror:

— Comrade Captain! Look at yourself!

I looked and saw that I was covered in oil…

— What are you trying to show me? Do you

think that I have never seen my reflection before?

And at this moment I finally saw what he meant

– I had become gray haired! But the photos I brought home were great!

— Whose fighters attacked you? German or Finnish?

Brewsters, FD, and Messers. The FD and Brewsters were definitely Finnish.

Volkov told me, and I saw it myself. The Messerschmitts could be German.

Who actually hit me — I don’t know.

— In your opinion, what was the top speed for Il-2?

220–240 kilometers per hour. That’s in straight, level flight. We could

reach more then 500 km\h in a dive.

— 220? Not 320 or 400?

At the front — 220–240. There is a difference between top speeds that

test pilots show in the test center on a “naked” plane, which weights 2

tons less. It is a completely different matter if a combat pilot flies

the plane with full load[12].

— You were covered by the same fighter regiments?

Twice HSU Pokryshev covered us [159th Fighter Regiment]. I used to

have photos where we are pictured together, but I can’t find them.

— Did fighters cover you on every mission?

Sometimes they did, sometimes they did not. If we received a difficult

task, or if the whole regiment flew out, then we would get

cover. Sometimes they would even go to the target before us, and leave

it after us. It happened quite often when we attacked airfields in Estonia,

west of Pskov. The closest village was Pomeranye, if I remember correctly.

We were hit rather well there in spite of fighter cover. But we paid them

back.

— How effective was fighter cover?

Even the presence of our fighters helped us. German fighters were not

so eager to attack us, and they didn’t interfere with our work.

— But it happened that Germans would get through the cover and shoot

our Shturmoviks down.

Anything could happen. Once, it was in Estonia, a fighter from our

cover shot down a German fighter that was already firing at me. Later he

told me: — Pray for me! I took him off

your tail.

— Were there cases when fighters would leave you for some reason?

No, there were no such cases.

— Were you stationed at the same airfield as the fighters, or separately?

Separately, but they were based near by. When we received a mission,

regiment commanders would call each other and discuss the details.

— Who was more dangerous to you? AAA or fighters?

Fighters. If we flew in pair or in a four-ship formation without cover,

they could have shot down one or two of our planes.

I remember when we had already liberated Novgorod, and it was time to liberate

Pskov. German fighters were annoying us, but we couldn’t find their airfield.

I, along with one of my comrades, I still remember his face and name –

Khristolyubov, was given a task to find this airfield and make a photo.

When we crossed the VelikayaRiver, we gained altitude. We looked for this

airbase, but it was well camouflaged. We found it only when we noticed

two dust trails – fighters were taking off to get us. We made photos and

dove to ground level. But they caught us and shot my friend down. They

tried to shoot me above LakePskov, but I made it home, alone[13].

— How did the Germans attack you? In pairs, or in large groups?

With two–three pairs, in turn. One pair attacks, another watches for

the results.

— How did Il-2 withstand battle damage?

Good plane, nothing else to say. Very tough. I already told you that

I took five 37mm shells, but I still made it home.

Here is another event. Between Novgorod and Staraya Russa there is

a village Mshinsk. Near this Mshinsk, Germans built a railway in the forest,

which was used for an armored trainmovement. It shot at our ground forces

and reduced the speed of our offensive. Our

squadron commander Belov received an order: find and destroy this train.

I flew as his wingman. We loaded up four or five FAB-100s each and took

off. We flew in this general area, and finally we spotted a slight trail

of smoke from the forest – it was the train.

We attacked it, they shot at us. “Wham!” and I got a hole in the wing.

My plane started to roll to the right. I informed the commander about the

damage: — Nikolay, I’ve got a hole!

He ordered me to return to base. When I landed, I got out of the cockpit,

onto the wing, and descended to the ground through the hole in the wing.

|

Damaged Il-2 from 872 ShAP. Pilot unknown. |

— Did you hit the train?

Because of the damage to my plane, we couldn’t confirm the strike results.

Most likely – yes. Any way, we never received it as a target from ground

forces.

— Which shells were not dangerous to the Il’s armor?

The armor around the engine could withstand a 37mm shell hit. It only

left a dent. I can’t say more. I was never hit by a larger caliber shell.

Those who were hit never returned [14].

—Did your regiment use the practice of deploying a part of a strike

group against AAA? For example, 2 out of 10 planes would strike AAA.

We didn’t try to especially strike AAA. We had a designated target,

and it got all the attention. We only used maneuvers against AAA.

For example, in the Mga area we had many targets—there were a lot of

fortifications. AAA was stationed 3 or 5 kilometers away, but they shot

well. They started shooting only when we approached our target. White explosions

– its small caliber AAA, black – large caliber AAA.

I didn’t understand what it was after the first two missions. I even

was interested, what were these beautiful “flowers.” On the third mission

I finally tasted it to the full extent. When your ass gets shot up, then

you immediately understand everything.

—Were you bombed at the airfield?

Where did this happen? It was early in the morning, but where? We didn’t

see who bombed us. From PskovLake some bastard flew to our airfield and

strafed it. It happened only once. I don’t remember where[15].

—You told us about an intensity of combat missions up to 4–5 per

day. When did you experience this intensity?

If an operation started, for example Mginskaya, or lifting of the blockade,

Narvskaya operation, we would fly very often. At the Karelian Isthmus we

also flew 3–4 missions on the first days. When the enemy defense line was

breached, we would start flying in pairs or fours. At this time we usually

had one sortie per day.

— Were there cases of striking our own troops?

Striking our troops? What for? There were Germans for that, and they

were good at it. If we would help them, it would be something ridiculous.

— By accident, or something.

Hit our own troops by accident? Yes, I heard something about it, but

not in our regiment. Before each sortie the chief of staff gave us the

frontline position. Every change was updated.

— HSU Yevdokimov told us how he bombed our forces by mistake.

Yevdokimov served in a long-range bomber unit, and he flew far and

high. We flew right above the ground. We would bomb and strafe the enemy

and fly back at tree-top level.

— We read that at the beginning of the war shturmovik pilots

flew very low.

We flew as low as possible for the duration of war. But you can’t

fly low at the target, and we made a “jump” before target. There were always

exceptions. When we attacked airfield near Pomeranye we kept flying low:

we just dumped our load of granulated phosphorus at the warehouses from

low-level flight.

— Did shturmovik pilots participate in dogfights?

We were covered, and there was no need for engaging enemy fighters.

— But if an enemy plane would appear in front of you, did you

press the trigger?

No, there would be no problem in pressing the button, but how

did the dogfights usually happen? In Estonia we were attacked by fighters,

and the command post calls: — Form a defensive circle, fast!

When we are in the circle, we defend each other. Gunner covers our

tail and the plane behind us. I defend the frontal hemisphere of our plane

and aircraft in front of us. As long as we are in the circle, no one attacks

us – we will easily repel any attack, and the Germans were not so stupid

as to risk their lives. So they would leave.

— Do you know of any cases when a shturmovik pilots shot an enemy

aircraft down?

To be honest – I never heard of such cases. Shooting planes down was

not our task.

— Can you tell us, what was your least-liked mission type?

Straight away: airfields were extremely dangerous targets. They were

heavily protected by AAA and fighters. I think that all pilots will tell

you the same.

It is much easier to strafe the front line,

or hunt down trains. Reconnaissance missions were also easier.

|

Petr Glazkov,-,-, Vasilii Tomarov (HSU),-,-,-, sitting SqC-3 Nikolay Platonov |

— What did you receive bonuses for?

We were paid for combat missions, for 30, 50, 80 missions.

— Were you paid for destroying targets?

No, never heard about it.

— How precisely could strike results be estimated?

By photograph! I told you how I was a photographer when the Finnish

airfield was hit. I brought home a film. When it was processed, they made

a composite photograph, and our specialists looked at it: — Here, this

one is on fire, this one shot down.

They checked everything, and told us: —Good work!

— Do you remember how your planes were painted?

They all were camouflaged, with a star.

— Green–green, black–green, green–brown?

Different greens with grey and yellowish-brown. If it was moved under

the trees, then you wouldn’t see it at all.

—When you received new planes at the factory, did they bear a tactical

number?

No, those were drawn in the regiment.

— What was the number color?

Red, all the same for all planes.

— Any fast recognition elements?

No, they were all the same, except tactical numbers.

— Did you have insignias on the sides of the fuselage?

No, nothing like this. But from the end of 1944 we began to draw pictures

on the fuselage sides.

Dmitriy Andreev used to have a picture: a crawfish stands on his tail

and holds a tankard in his clamps, and foam is dripping from the side.

— Did regiment or division command forbid these drawings?

No one was against it. Batya saw this crawfish on the fuselage, and

laughed: — Germans draw dragons and tigers, something scary in other

words, and here we have a crawfish with a tankard of beer…

And my technician drew a heart in place of the left fuselage star

— Do you remember who your technician was?

There were several of them.

— Did you officially receive a plane before the mission from your

mechanic?

Yes, how was it done? Chassis, flaps, aerilons. Then I would start

the engine, test it on the ground, and check the instruments: oil

pressure and fuel pressure, temperature. Then I would sign in the plane’s

logbook. This is what “receiving the airplane from the mechanic” means.

When I would return from a sortie, I would tell him: — Do this and

that, check those tubes for leakage, and don’t forget to grease this part.

— What is your attitude toward ground crew?

The best. How can I think badly about them, if they prepared an aircraft

for me?

Do you remember how in the movie «Only Old Men Go to Combat»

the old technician says to the young one: — The most difficult part

in our work is to wait for them to return.

— How you were fed?

At the front, everything is completely different than in the rear.

We were fed pretty well, and those who flew combat missions would

get their 100 grams [of spirits].

— Did you try to expand rations yourself?

But where? The Germans left the ground burning behind them. At some

places there were berries left… Besides, we had no time for

that.

|

Ulyanovskii, Rymar, Platonov, -, Belov |

— Were a combat 100 grams given per each mission flown, or per day

independently of the number of flights?

It was given to us in the evening, when we flew at least 2–3 missions

per day. We would fly intensively for about a month. And we

would lose half of our planes during this time. When we were not flying,

we were not given these 100 grams.

— If you felt that these 100 grams were not enough, could you find

some more?

You know what happened? We were issued our 100, but some festivities

were coming, we would say to our waitress: — Katya, preserve my 100

grams for later use.

And on the following days the same: — Katya, keep these also, and

give us all of it on the holiday.

— Did you buy alcohol from the locals?

I drank it, but I have no idea where or who got it. Estonian

“moonshine” was better than our vodka. It was like tea with alcohol. Tasty

and

burns, if set on fire. Sometimess you’ll drink vodka and it will burn

as if a knife cut.

— Did you drink “liquor chassis”[16]?

Technical crew members did, and I also drank it. But much later, when

I was flying in transport aviation. The Li-2 had “de-icing liquid,”

which was pure spirit – 96 degree. 92 were considered as spoilage.

— Do you remember if anybody would fly drunk or with a hangover?

It was forbidden, and Batya was very cautious about it. He used to

come every day at 22.00 sharp to our living apartments, check our presence,

and each day he reminded the duty officer: — Make sure that no one leaves.

That’s because we had to fly on the next day, and if someone would

go to the girls, or get drunk, he would be unable to fly. But I do remember

one such case. Dmitrii Andreev told us: —I’ll go for a walk to India.

For some reason he called Estonia India. He got drunk, and brought

a bottle of moonshine with him. He was caught, and didn’t fly several missions.

Because of this story on his record, he wasn’t awarded HSU. I don’t know

what happened to him. Later, we went different ways.

— What were your living conditions?

Different. When we lived in Gremyachevo, we were living at the village

in different houses. We slept in sleeping bags. Conditions varied: we used

to sleep on the roofs, on two-tier beds. Even on the tree branches. Once

we flew to the new airfield, but the airfield servicing battalion was lost

behind, so we had to sleep for three days on the street. It was late November,

the ground was frozen solid, and we slept in a hay stack. We didn’t even

undress from our warm flight uniforms.

Sometimes we lived in dugouts. We had two-tier beds, with hay mattresses,

covered by canvas, and on top of it all were our sleeping bags.

We used to have barrels with chimneys to keep it warm. And Batya would

come to check on us in the evening. Here he is – Nikolay Terentyevich Kuznetsov.

He was a Moscovite.

|

Titovich, Platonov, Nikolay Terentyevich Kuznetsov, former Polar aviation pilot, commander of 872 ShAP, Ulyanovskii, Andreev, Tomarov |

— Were there animals in your regiment?

Of course! There was a little dog, our mascot. Its name was Dootik

(slang for tail wheel). Everybody tried to carry it in their arms, and

we kept bringing it with us to the new airfields.

— Actually, I meant another “animals” – were there parasites, such

as lice?

No, I can’t recall any cases. We were given new uniforms regularly,

each 10 days we had to go to the sauna.

— Were there concert teams coming to your airfield?

They did. Two or three times during summer. But we were young boys,

and we didn’t know who visited us. We found out that Tarasova

was famous, and Orlova was the most famous only after war’s end. Then

we knew nothing. They would sing songs and dance for us, and leave. And

we stayed there to keep fighting.

— Did you have vacations? Did you visit Leningrad during war time?

What for? We stayed with the regiment for the duration of war.

— Were there recreation facilities for flight crews?

During the war? No, I never heard about them. After the war we had

recreation facilities. Each year there were two month for vacation.

You were obliged to spend the first month in some sanatorium, where

you would get all the medical attention you needed, so that your health

condition would allow you to keep flying. You could spend the second

month of your vacation as you pleased. But when Nikita Khrushchev came

to power, he began to give us “presents”: at first he cut our vacation

by 15 days, then he made cuts on our “years of service” records; we were

stripped of the privileges that Stalin had given us, and then he stopped

“award payments.”

— Were there many women in the regiment?

Here is the photo – all the women of our regiment with the regiment

commander. We had five or six women who armed our cannons and machine guns

and looked after our parachutes. This photo was made on 8th of March.

|

March 8th 1944. Kuznetsov with regiments women. |

—Were there cases when someone fell in love with them?

Well, yes. Usually it happened when there were no active operations

on our hands.

— What was your attitude toward political functionaries in your regiment?

Were they pilots?

They were different. It all depended on the person. In our regiment

the commissar was Major Panyushkin. He didn’t fly himself, but he was very

easy-going with people and paid a lot of attention to us. You felt like

you had talked to your own father after talking to him.

— Were they needed?

I can’t say exactly, but they at least didn’t interfere.

— Was there a Special Department in the regiment?

Yes, there was one representative. He looked after us, who went where,

who did what. But I can’t say that he caused us any trouble. We saw the

results of his work only once. After Kuznetsov was killed, he was replaced

by ex-ZAP commander Zeselson. He had no combat experience at all, but he

started teaching us how to fly. Pilots complained about his incompetence,

and this osobist helped us to get rid of Zeselson. I have no idea what

happened to him next. Kuznetsov was the best commander that could be.

— How many missions did the gunner have to fly to be awarded, let’s

say, the Order of the Red Star?

The gunner awarded by order for mission quantity? I don’t remember

such cases. If he shot down an enemy fighter – then yes, it was possible.

— What was your attitude toward the Soviet Government before and

during the war?

At that time we never knew another kind of government. But we liked

the one we had. On the other hand, I don’t like the regime that was made

by bold lousy combine operator (reference to the fact that Gorbachev was

responsible for agricultural sector once), Gorbachev, whith this Kravchuk

and Yeltsin. There is a good saying in Russia: God marks the rascal.They

broke down everything we fought for and built after the war. They claimed

to prevent a revolt. But a revolt is was what they made.

|

In front of a trophy Mercedes and Harley-Davidson. Both were discovered in a hay stack after liberating Karelian Isthmus. 1st Squadron adjutant Golshukov, Dmitrii Andreev,-, Tomarov, Titovich, Zaizev, -. |

— Tell us, what was the relationship between different nationalities

in your regiment?

We had people of different nationalities, but there were no nationality-related

problems. Everyone was judged by their work results. As long as you worked

well, it didn’t matter if you were a Georgian, Ukranian, Armenian, or Kazah.

It was all alike in the ground forces. Before each operation we were loaded

on the trucks and brought to the frontline, so that we could see everything

from the infantry point of view. This was done in order to avoid strikes

against our ground forces. There were all nations

of the Soviet Union in the trenches. Here and there one could hear:

— Cazo, leave me a cigarette stub.

— How did Estonians accept you?

Open heartedly. We were considered to be liberators. We were stationed

at Tartu, Pyarnu, and Hapsala. And I can’t recall a single bad

word said toward us. I only remember that in Tallinn there

were cases when Estonian fascists killed several sailors in the city park.

— Do you remember when you received the Il-10?

At the end of the war. And we didn’t like it for some reason. It was

very unstable, especially on the final approach. We felt that it was

about to spin out of control. The Il-10 was removed

quite soon from our regiment, and we returned to flying the Il-2.

— What type of aircraft did you flew after the Il-2?

The Li-2. After the Il-2 I flew the Li-2. As war ended, regiments began

to be disbanded. At this time I was the deputy Squadron Commander, a Captain.

I went to the 13th Air Army chief of personnel, Colonel Rostov. He said:

— There is too much military aviation. We have to reduce its quantity.

There is a country to rise from the ashes, and too few men left. I don’t

think that I will be able to find a place for you in aviation.

I replied: — I won’t leave. I dreamed

of becoming a pilot from my boyhood, and now, when I finally can say that

I learned everything, you are going to

demobilize me. No pasaran![17]Any place will be good for me, but

I have to remain flying.

After two months, I went back to him — “No positions.” For two

month I received my salary, and after that I was paid only for my awards

and rank. But I decided that I would fly even if I would have to wait

for a year. Regardless of anything! After four more months, they found

me a

place as a second pilot in a Li-2 crew at the «court» squadron

of Leningrad Military District. It was based at Levashovo. My crew commander

was

Nikolskiy.

— Let’s go back a little bit. When you were told that a second front

had been opened, did you feel any ease? Or was it unimportant to you?

How did we feel about it? We were simple pilots, not some high ranking

officers. I can say that we were offended by the absence of the second

front from the very beginning. They opened it when we were at the gates

of Germany: — Hurray! We are going to

help Russians!

By this time there was no need for help. It was needed two years earlier.

I heard the following words from a former Il-2 gunner:

—What good was this second front for us? They invaded France, but they

had no idea how to fight modern war. The Germans kicked them again and

again, so Churchill and Eisenhower kept asking Stalin to press on out front,

to relieve German pressure from them. So we had to start new offensives

without proper preparations just in order to save our allies.

That is, Allied success on the Western front was paid for by Russian blood

on the Eastern front.

We were not talking about this at the front, but I came to the same conclusion

after the war.

— How did you find out that you had become a HSU?

It was complete surprise for me. I didn’t even know that someone had

recommended me to become HSU. We were at

Pyarnu then. Suddenly the regiment commander said:

— Here is a newspaper, I’ll read. We have Heroes!

And he read. In Pravda or Izvestiya newspaper was a list of those who were

awarded HSU and Orders on February 22.

— How did you celebrate this event?

We did not. It was just an article in the newspaper. We celebrated

after I returned from Moscow with the medal. I was summoned to Moscow

to receive the award. Everything was arranged well. By the required time

I was in Moscow, and I was handed the award in the Kremlin.

— Were you a captain by this time?

Yes. I was awarded along with 10 other people. Awards were handed out

by Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin. Just before the procedure, Lacis, from Riga,

came to us: — You came from the front

line, and you are young and full of strength. Kalinin is old, and he will

only hand awards to the HSUs. All the

rest will receive their awards from me.

When I returned to Parny, I was called forward at the morning formation:

— Come out of the line, and tell us how you received your awards.

But I suddenly became shy. I was pushed and found myself in the middle.

Istarted talking: — Kalinin gave me the

award. Oh, instead of talking, I would prefer to fly ten missions. Let’s

stop this chit-chat. And at this moment,

they grabbed me and started throw in the air… And

we “polished” my Star with “moonshine”, and we “polished” it well.

— Did your title change other men’s attitude toward you?

Nothing changed. If you were a Hero those days, it meant that you were

expected to fly the most dangerous missions and complete them. There was

no envy toward us, but a lot of respect.

— How many Heroes there were in your regiment?

There was a photo: Regiment commander and the five most experienced

pilots. If five pilots were awarded HSU, then the regiment

commander would also receive HSU. I became HSU, Komarov, Malinovskiy, Fedyakov,

and Ulyanovskiy. But our commander didn’t become a Hero. He was killed

in Estonia. He was killed so absurdly… It was a pity.

In February 1945, we were stationed at the Tori village in Estonia. Kuznetsov’s

wife came to visit him on Red Army day.

The commanders arranged something to be given to us from the Voentorg

[military sales store] for festivities. The commander said to me:

— Take the U-2, remove the back seat, load it with crates, put the Voentorg

saleslady on top of them, and fly to Tallinn.

We flew to Tallinn, where we loaded up with vodka, cognac, Kazbek - famous

cigarettes. And we flew back. It was a scary,

horrible coincidence. I returned to the regiment, landed, and taxied to

the parking area. As I stood up in the cabin, I saw two airplanes collide

right above our airfield. We had received

replacement pilots, and they were practicing. Nikolay Terentyevich also

was doing a check ride with new pilot in the UIl-2, and just as they were

coming in to land some young pilot dove right into their plane. All that

I brought to celebrate with — we drank at the funeral.

His wife came to us as a wife, but left us as a widow[18]. Here is the

photo.

|

The last photo of Kuznetsov taken with his wife a few hours before his death. It was a universally bad omen to make photos before take off. |

— Who could also have become a Hero?

I don’t know why Nikolay Platonov and Andreev didn’t become a Hero.

— Was there any particular reason why your regiment didn’t become

Guards?

We flew a lot, we accomplished many missions. All the necessary requirements

were met. I have no idea why we were not given Guards status. But it was

not a matter of concern to us in those days. We thought only how to fly

and kill the enemy. I never thought that I would receive HSU. My job was

simple – fly where told, drop bombs and, if possible, return home. All

titles and medals are just the side effects of this work.

Our first Heroes were Levanevskiy and Lapidevskiy. They were also given

a car, 25,000 rubles, and apartments in Moscow. By the time I received

the title, it meant only that I was given a “Golden Star” medal and an

Order of Lenin. I never thought that later I would have some privileges

and benefits.

|

HSU Fedyakov after 150th sortie exiting the cockpit |

— How were radio communications arranged in your regiment?

At first there were no radio transmitters, and we had two-way connection

within the crew only[19]. There used to be

a receiver, but its quality was very low. There were more squelching sounds

than actual talking. Later we received full radio sets. There were preset

frequencies, but it was still difficult to use it – sometimes you couldn’t

understand if this transmission was directed to you at all. Only by the

end of the war did radio communications become more or less adequate.

For example, I heard very well when our command post called me, and I was

at that moment near Ezel Island: — There

are two ships at sea, do you see them? Can you get there and fire at them?

I replied: — Sorry, I can’t swim.

I mean, naval pilots had special equipment, so if he got shot down, he

could swim. We army pilots didn’t have any such equipment.

— Were you afraid to fly above water in general?

fraid? No, we quite often flew above the Gulf of Finland! But we flew

as close to the shore as possible, so that we could make it to the solid

ground. There was no appropriate equipment to fly far into the open sea.

Besides, water in the Baltic Sea is cold.

— Did you maintain radio silence, or were you talking at will while

you flew?

No, when we took off we had an order:

– Everybody shut up, only listen!

Only the flight leader could break radio silence, but he would keep silent

until we reached our target. This was done to prevent Germans from detecting

our presence. For this same reason we always flew low. Near our designated

target, we would rise up to 800 meters, strike our target, and return to

the base again at tree-top level.

— How did you gain altitude? By a steep climb or by a shallow one?

By shallow climb, which we usually started somewhere near the front

line, so that we would be changing altitude when we came under small caliber

AAA fire. When you fly low and level, there will be no need to make adjustments

for those who shot at us. Besides, at low altitude you are being shot at

by all possible weapon types.

— Were you told that Germans had radars?

No one told us about it. You talked to Yevdokimov. He flew at altitudes

of 3–5 thousand meters, and it is possible that they were warned. But we

flew at tree-top level, and there was no need to warn us.

— In the old chronicles you sometimes can see that a group of Ils

flying at the altitude of 2–3 meters above ground. Did you fly in the same

manner?

Yes. That’s how we flew. It was called “wiping roads with propellers.”

In this case, fighters won’t be able to get below me, and from above my

gunner will cover the rear hemisphere, while I will be able to cover the

frontal one. So, flying low is safer. Sometimes.

— Did your gunner shoot down any enemy planes?

He shot at them, and even hit some, but did not down any.

— And in the regiment?

I remember one such case.

— And how was this gunner awarded?

I don’t remember. If I knew that someone would be asking such

questions, I’d have taken notes.

— 150 rounds of ammo for the rear gun—was it enough?

It was quite sufficient. Because we mainly flew in groups, and

the Germans were not too eager to attack groups. In Estonia their fighters

intercepted us several times, but we formed a “defense circle,” and they

didn’t even come close to us.

— Did you use a “scissors” maneuver?

Scissors? Yes, we knew this maneuver, but we didn’t use it.

— What was the minimum amount of planes to form a “defense circle”?

Four to six would be enough[20].

— What is your opinion about Finnish and German fighter planes and

pilots?

They both shot well. They hit me well that time near Vyborg, so that

I barely made it home.

|

Tomarov,-,-, Ulyanovskii, Strelnikov Anatolii, Titovich |

— They hit you once, while you bombed them many times?

We bombed them by six-plane formations, and this was a completely different

story.

— One can read in German memoirs something like this: “The Russians

came in a crowd, no less then a hundred aircraft. Our pair took off, and

started shooting them down one after another.”

But when you read memoirs of our pilots, they all state the same: “Germans

would attack only when they had numerical

advantage.” What was your experience?

Interesting question. I’ll answer this way: They would attack only

when they felt that their attack would be successful. I already described

to you how I flew the photograph mission alone. At first one fighter pair

appeared, but they didn’t attack. They just kept track of me, and only

imitated a dogfight. For showing off in front of their superiors, I presume.

Only after two other pairs came did they altogether started firing at me

seriously. I made a lot of wild maneuvers, but I managed to get away from

them only because I made it to our AAA site.

— Can you take a look through this loss list of your regiment?

Let’s see... Belov, Nikolay Andreevich, captain, squadron commander.

I was in his squadron. “Did not return from mission, shot down”[21].

He was shot down south of Pskov. He fell in the area between Snegirovo,

Nekloch, Dubyagi, and Tyamsha. We were striking

the front line. There were no AAA and fighters here. He dove, shot, and

dropped bombs. But for some reason he didn’t pull out. His plane didn’t

explode on impact, but broke into pieces; the engine flew out to 20 meters.

I flew above and made a photograph of his plane. I brought four other planes

with me. When we approached Zhelcha airfield, which was located south of

Gdov, we had to identify ourselves over the radio. It was working well

by this time. They asked: — Who’s absent?

Who’s leading? — Titovich leading.

We lost him.

When we landed, they gathered around, and kept asking: “Where?”

I said: — Process the film.

They took the camera to our photo specialist Petr Savanovich, and he

made photos. I had flown very low, and everything was clearly visible:

Their territory, trenches, and the plane broken into several large pieces,

the engine lying separately on the ground. But I’m pretty sure that no

one was shooting at us.

|

Squadron Commander-1 Belov |

— Do you think that Belov committed suicide?

He was a completely different type of personality. He either lost consciousness

for some reason, or something happened to his plane.

Let’s go on. Davydov Mikhail. We were flying from Vyborg, and he simply

disappeared. I have no idea what happened to him[22].

— Where did he disappear?

It’s hard to say. We were returning from the Karelian Isthmus, after

striking targets in general area of Vyborg. We noticed his absence somewhere

near Zelenogorsk. Our base was at Levashovo then. We usually flew above

forests, and 3–5 kilometers to the left from Zelenogorsk I suddenly noticed

that one aircraft was missing. I suggested we form a circle. We made 2

or 3 circles, and kept calling him over the radio. No reply. No sign of

a fire on the ground. He was listed as MIA.

I reported to the regiment commander:

— Mikhail Davydov was lost without a trace!

— What about Mashkovtsev[23]?

It was Mashkovtsev who covered me on that reconnaissanse mission, not

Khristolyubov! It was Mashkovtsev on my wing! We called that enemy airfield

«Devils pipe». I made photographs, and when we were flying

home, they shot him down. "Remains found near Babino in 1950." Right, it

was Mashkovtsev. I never saw what happened

to him, because I was trying to escape from two fighters above PskovLake.

At that moment I was only thinking how not to catch water with my wingtip.

“Strelnikov Anatoliy. Remains found.” He used to live in Moscow before

the war. When we flew to Kuybyshev for new airplanes, we used to

stay at his home for a day or two. He was killed during the Narva operation[24]…

—Did you see how it happened?

No. If I’m not mistaken, I wasn’t flying when it happened.

— Have you seen how your comrades were shot down?

I saw with my own eyes how my best friend Nikolay Tripolskiy was shot

down. We came to the regiment together, and we both were living in Kramatorsk.

Here he is, in the photo: we studied together in one school, in aero

club, in the flight school, and we fought at the same squadron.

On that day we flew together, I returned, while he did not. On that

day I flew a reconnaissance mission to the Pechory area, and found an airfield

there. Later that day we flew in six-plane formations to strafe it. That

was something! There were no fighters in the air, but AAA fire was immense!

The entire airfield was covered by small caliber AAA shell explosions.

There were some new shells there – with blue clouds instead of white. His

plane was hit by AAA, and his engine started stalling. One “leg” [landing

gear] fell out. He started descending. Tripolskiy landed near the forest

on the other side of VelikayaRiver. His gunner launched a flare, which

was a signal "we are alive." And that was it. We never heard about them[25].

—Have you seen any other planes go down?

No, usually we would turn our heads around, and suddenly someone would

notice that one plane went missing.

— It is a common belief that for each pilot lost, an Il-2 regiment

lost seven gunners. The idea is that pilot sat in the armored tub, while

gunner was not properly covered.

How much!? I may not be exactly precise, but I can’t recall if the

pilot brought his dead gunner to the airfield. If an aircraft was shot

down, it usually took both crew members with it[26].

— Question about your instructor Lyapin. When was he killed—before

you came to the regiment, or after?

I was told that he was sent from the flight school to the combat

regiment to gain experience. When I came to the regiment, my first question

was about him. They told me: — He was

killed a day ago in Lyuban-Tosno area. How it happened – we have no

idea. (Look at the appendix for extra information)

|

Voroshilovgradaviationschool, April 1943. Instructor Lyapin (in a cone-hat) with his cadets. |

— Were there cases when a pilot who had been shot down behind

enemy lines later returned to the regiment?

If they were shot down, they did not return.

|

Airfield Tori, winter 1944. Closest airplane – Uil-2. Titovich holds the banner. |

|

Same location. Note FRE – half of the spinner painted in white on some airplanes |

— How did you found out about the war’s end?

Oh! People were cheering! It happened in Estonia. At four o’clock

in the morning we were sleeping with open windows. Then, suddenly we heard

gunfire, and a wave was coming close to us. People started shouting. Then,

at 6 o’clock it was announced over the radio: The Great Patriotic War,

that lasted X number of years, month and days, IS OVER! At this moment

people started kissing each other, crying, and shouting. In a few moments

alcohol appeared on the streets. And we started to drink, with one toast:

“For Victory!”.

Yes… Victory… And so many of our friends did not make it.

Appendix

(Researched and provided by Ilya Perokofyev)

Let’s try to briefly explain what happened on July 27 1943 during strafing

of the Borodulino airfield.

Two Il-2s from 872nd ShAP took off for a free hunt mission, crewed

by Maximov-Chuprov and Lyapin-Kuzmin.

Their cover was provided by three Yak-1b fighters from 287nd fighter

regiment, lead by Seniour Lieutenant Borisov.

Aproximately at 1800 hours shturmoviks found suitable targets near

Borodulino airfield and started strafing and bombing them. Altitudes were

from 1200 to 50 meters. At this same time three Yaks that were supposed

to cover Ils were tied up in a dogfight with a numerically superior enemy

fighters.

As it is described in the fighter regiment

documents, they were attacked by a group of FW-190 and one Me-110. This

mixed group tells us, that most likely the enemy fighters escorted a reconnaissance

aircraft, which flew out, or was about to land at Borodulino. Dogfight

was taking place at an altitude a lot higher then the one that was used

by shturmoviks. It had no results for both sides. Meanwhile, both Ils were

damaged by AAA fire. Some of the fighter pilots noticed that one of the

Ils had turned to the enemy, and fully under pilots control had rammed

an ammunition dump, which was located at the side of the airfield. Second

Il-2 pulled out and headed northwards in the general direction of Ladoga

Lake. Due to the large difference in altitude none of the fighters could

see the tactical numbers of the planes. For unknown reason it was decided

by the regiment commanders that it was Maximov and Chuprov that rammed

the ammo dump. In 2007 wreck of the Il-2 aircraft and the remains of the

crew were found in the marshes 40 kilometers north from Borodulino. After

remains were unearthened, there were documents found on the corpses, which

showed the name of Chuprov.

It is a confirmed fact that there was a “fire

ram” at the Borodulino airfield in the summer 1943 (As the locals described

it – there was such a huge explosion, that all women of the village for

three days had been washing German underwear)!

Based on these facts it is evident that the

fire ram was conducted by Jr. Lieutenant Lyapin Ivan Panteleevich and his

gunner Seniour Seargeant Kuzmin Mihail Mihailovich.

[1]Fabrichno-Zavodskoye Uchilishe. It was a technical school that belonged

to some plant, where students would receive profession while practicing

at the plant. O.K

[2]Novokaramorsk machine-building factory

[3]The Donbass Proletariat military flight school in Voroshilovgrad

trained SB pilots up to the middle of 1942. 959 men completed training

during 1941, and 129 in 1942. Beginning in 1942, training was done on Il-2

aircraft, with 141 graduates that year, 550 in 1943, 848 in 1944, and 179

in 1945; 50 pilots were trained to fly R-5 in 1944. O.R.

[4]SB aircraft had no self-sealing tanks or “inert gas” tank-filling

system. O.R.

[5]There were ellipses on the windscreen armor, an aiming mark in front

of it, and there were white stripes on the cowl. O.R.

[6]Each school had it’s own small museum, which covered a combat way

of a single unit. Sometimes these “rooms” had a greater documentary and

photographic collections then official museums. After 1992 most of these

museums were disbanded by the order of the Ministry of Education, and all

the precious documents were simply thrown away as garbage. O.K.

[7]In all documents regiment commanders stated that Il-2 was not suited

for flying in bad weather due to poor visibility from the cockpit. O.R.

[8]It was generaly considered that pilot was young for first 10 missions.

O.R.

[9]VAP — vylivnoy aviatsionnyy pribor – liquid aviation device - a

spraying apparatus normally associated with chemical dispersal

[10]Il-2 with 37mm cannons was never built with metal wings. Il-2 withNS-37

production was cancelled in November 1943, and Aviation Plant N30 at this

time built planes only with wooden wings. O.R.

[11]In both oil tanks there were 65-71 liters of oil. O.R.

[12]240 km\h — it was a speed of maximal range. On average Il-2 flew

with a speed of 320-340 km\h. O.R.

[13]Jr. Lieutenant Hristolyubov Artem Alexandrovich, born in 1922 was

shot down by enemy fighters on 02.04.1944. Buried in village Novoselye

of Strugo-Krasnenskii district of Pskov oblast. I.Z.

[14]Most likely, he tells about 20mm shells, or about 37mm hitting

at the maximum range, when shell lost it’s power. At the shooting range

tests 37mm shells penetrated armor of Il-2 at any angle. O.R.

[15]872 ShAP had lost only two gunners Pupkov Alexey and Yarcev Semen

Yegorovich to the strafing of the airfield on 5.12.1944. I.Z.

[16]Mixture of a syrup and alcohol from filtered landing gear brake

fluid

[17]An expression which dates back to Spanish Civil War – it literally

translates as “they won’t pass”, and is used when one want’s to say that

someone will be unsuccessful.

[18]On 22.02.1945 in a mid-air collision above airfield two crews had

perished. 1st: Regiment commander Lt. Colonel Kuznetsov Nikolay Terentyevich

( born in 1905, at Brest-Litovsk), Jr. Lieutenant Serdyuk Alexandr Ivanovich(Born

in 1923, Stalinskaya oblast.) 2nd:Jr Lieutenant Shkurnii Ivan Alexeevich

(1922, Bryanskaya oblast) and gunner Uspenskii Lev Evgenyevich (1926, Arzamas).

Buried 4 km east of Tori, Pyarnu area, Estonia I.Z.

[19]SPU-2 or SPU-2f, the connection was very poor, with a lot if static

noise O.R.

[20]It was considered that no less then 6 planes were required, 4 were

not enough – distance between airplanes was a bit too large. O.R.

[21]Squadron commander Captain Belov Nikolay Andreevich and gunner

Pushev Vitalii Petrovich did not return from the combat mission on 15.04.1944

from the general rea of Pskov. I.Z.

[22]Davydov Mihail Mitrofanovich, Jr. Lieutenant MIA on 19.6.1944.

Gunner not identified. This day the regiment lost 3 pilots and 3 gunners

I.Z.

[23]Lieutenant Mashkovtsev Alexandr Vasilyevich and gunner Jr. Sergeant

Sharapov Dmitrii Ivanovich were shot down on 07.04.1944 in the Pechory

area by fighters. I.Z.

[24]Lieutenant Strelnikov Anatolii Gerasimovich and Senior Sergeant

Yakovlev Alexey Yakovlevich were shot down by enemy fighters on 24.07.1944,

remains found in 2001. I.P.

[25]Jr. Lieutenant Tripolskii Nikolay Vasilyevich and gunner Perepelica

Nikolay Semenovich were shot down on 08.04.1944. I.Z.

[26]Known losses for the regiment were 73 pilots, 45 gunners. In 1944

31 pilot, 29 gunners. I.Z.